The Bad Bunny Brand.

On how Benito Antonio Martinez Ocasio commercializes individualism in his music.

Be sure to share this article through social media so that more people can read it. I am sincerely thankful to my subscribers for supporting Borikén: Cinco Siglos de Lucha.

The ruling ideas of each age have ever been the ideas of its ruling class.1

Karl Marx, 1848

I became the owner of the world and I don't want to let go

That's why I don't give a damn2

Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, 2018

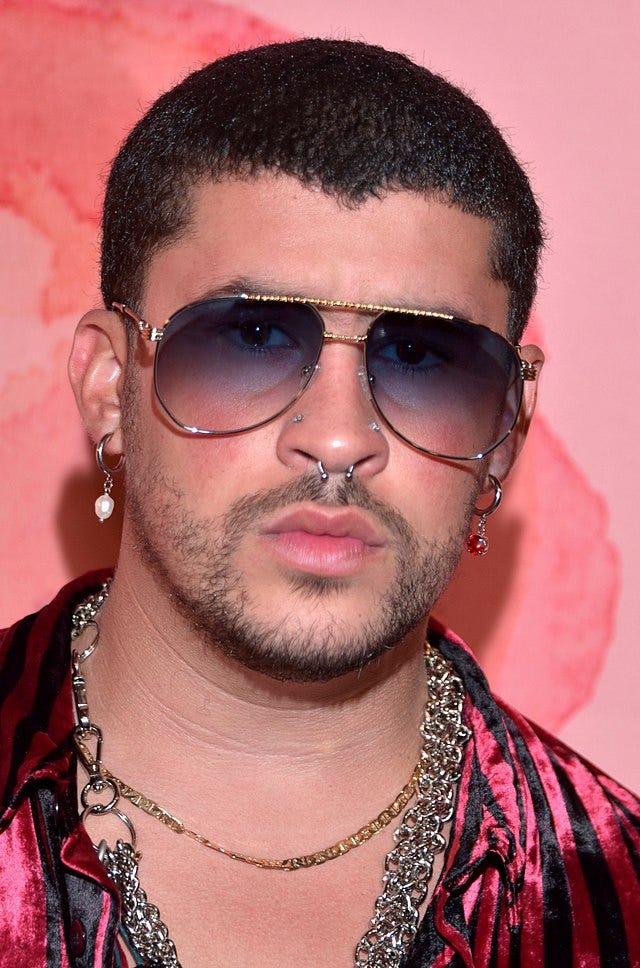

Bad Bunny in Los Angeles, California on October 11, 2019 (Wikimedia Commons) - Photo by Glenn Francis of www.PacificProDigital.com

Public discussion, both in Puerto Rico and in the United States, lacks such a degree of depth that one can ignore it for months and not lose anything important. Shortly after my first article of January of this year, I had in mind to do a commentary about the presentation of the Debí Tirar Más Fotos album of the Puerto Rican artist Benito Antonio Martinez Ocasio; better known as Bad Bunny. Said album, which was presented on the 5th of January, reached the number 1 spot on Billboard magazine’s list of most streamed albums in the United States. Given that I am not the biggest fan of Urbano music, I would have ignored this occurrence had it not been for the reception that the album had as an apparent symbol of Puerto Rican culture. Specifically, all the articles of the corporate press celebrated its mixture of traditional Puerto Rican genres like plena and música jíbara with reguetón. One of the songs of Debí Tirar Más Fotos, titled “Lo que le Pasó a Hawaii”, was even presented as a protest against gentrification in Puerto Rico and as a call to preserve the cultural heritage of the Island.

This coverage generated an environment in Puerto Rico where any critical observation about the trajectory of the artist was rejected outright with such solid arguments as: naming as “old people” all those who did not understand Bad Bunny’s “patriotism”, that the singer was teaching the new generations of Puerto Ricans their national history even though local teachers have been doing that for decades and of “elitism.” (Ramos-Perrea, 2025, 7, 8 y 10) A series of personal compromises prevented me from examining this subject and it remained in waiting for several months. In spite of that, the announcement made on January 13 that the artist will give a residence in Puerto Rico in July 11 of this year gives me the chance of analyzing Bad Bunny’s trajectory. One of the local corporate newspapers, El Vocero, estimated in January that such an event will have an impact of $100 million for the Island’s economy. For that month, even, 400,000 tickets were sold in only four hours and the artist added 9 additional concerts to the 30 that his team had already planned. All of this gives us an idea of the reception that Bad Bunny has received among corporate media and Urbano music consumers at a global level.

Of course, I am not pointing out these facts to celebrate the artist’s trajectory; but to contextualize it and raise questions. What made Martinez Ocasio have such a reception among music producers in the United States and Puerto Rico? What factors made Bad Bunny’s music have fans not only in Puerto Rico, but also worldwide? Finally, why is it that a segment of Puerto Rico’s intellectual sphere has baptized this millionaire as a defender and promoter of Puerto Rican culture? In the first place, it must be clarified that nobody can make a career in contemporary music through pure individual talent. All human cultural production is the result of a collective effort. Even in the distant past, artists depended of: the work of those who fabricated their instruments, the lessons of colleagues from previous generations, and the receptiveness of their audiences. But in the context of a society with social classes, an additional factor emerges. This consists that any artist who wants to live comfortably must get the sponsorship of the wealthy classes.

The way in which this is achieved is by reproducing the ideas of the ruling classes. The most famous example of it is the art of the Renaissance period between the XV and XVII centuries; in which talented artists competed for the sponsorship of wealthy patrons. Thus, such artists were compelled to cultivate disciplines as diverse as painting and sculpture; combining them with historical, anatomical, and mathematical studies to create works whose aesthetic reflected human beings in their natural environment. At the ideological level, however, that art projected the ideas of: the Catholic church, the high nobility, and the wealthy merchants. For example; The Birth of Venus of Sandro Boticelli was sponsored by the Florentine banker Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici in the 1480’s and represented a subject of Greco-Roman religion to increase the prestige of its patron. The Equestrian Portrait of Charles V of Titian is a painting that was sponsored by the Spanish emperor in 1547 to propagandize a military victory. The Pietà of Michelangelo is a marble sculpture that illustrates a subject of Christianity because it was commissioned by a French cardinal.

Many will be confused or horrified by daring to mention Bad Bunny’s music alongside a few works of the European Renaissance in the same assay. After all, anyone who takes the liberty of examining the lyrics of any and all of the songs in the six albums of this singer will notice that most of them explicitly celebrates individualism, profiteering and hedonism. For example, the subject of the lyrics in “200 MPH” of the X100pre album (2018) speaks about sex on the beach and going at 200 miles per hour on a jet ski. “P FKN R” of YHLQMDLG (2020) insinuates that criminality is the characteristic that defines Puerto Rico and celebrates it. “La Droga” is a misogynistic song from El ultimo tour del mundo (2020) album that equates an imaginary Ex girlfriend of the singer with a drug. Part of the lyrics of “El Apagón” of Un Verano sin ti (2022) says “let them go” without saying who are those who should leave the Island. It also says “I don't want to leave here”; in spite of the fact that Bad Bunny has a $8.8 million mansion in Los Ángeles, California.

Be part of the discussion; be sure to like and comment.

The song “Gracias por Nada” from the album Nadie Sabe lo que va a Pasar Mañana (2023) complains about the infidelity of an imaginary ex-girlfriend, even when the act of doing what one wants regardless of consequences is the recurring idea of the lyrics of these songs. Finally, the premise of “Voy a Llevarte PA’ PR” of Debí Tirar Más Fotos (2025) says almost nothing of Puerto Rico’s culture; but rather it deals about how Martinez Ocasio takes a girlfriend to a vacation on the Island to dance reguetón and have sex. I must emphasize that I am not a moralist and I am not scandalized by the content of Bad Bunny’s music. What was most impactful to me, after reading the lyrics of all his songs, was how well his musical repertoire represents the degenerate culture of the wealthy classes both in Puerto Rico and the United States. Beyond that, I could not find in any of these songs the Puerto Ricanness that corporate media and even some Boricua intellectuals talk so much about. The essay “La representación de la cultura en el imaginario colectivo puertorriqueño: Cómo Bad Bunny por medio de un intro de un concierto reescribió la historia de la identidad puertorriqueña” (2023) of Kristine Drowne is just one example of how the latter sector interprets the singer.

Using the introductory video of the concert “P FKN R” of December 2021, the author argues that Bad Bunny presents us with a counter hegemonic account of resistance through the affirmation of Puerto Rican culture. She also stipulates that Martinez Ocasio “has utilized his character anchored in mass culture, as in the unification of his power and participation on the means of communication and culture to propel through media culture a different cultural account”3 (Drowne, 2023) without even analyzing the content of the music that was presented in the concert. Both arguments condense the tendency, among liberal Puerto Rican intellectuals that endorse Martinez Ocasio as a promoter of Puerto Ricannnes, of focusing on any gesture of patriotism from the artist and the receptivity of his music worldwide instead of analyzing the content of his cultural production. In fact, the video that the author promotes as a counter hegemonic discourse is a mere decontextualized montage of images that include: Puerto Rican landscapes with their flora and fauna, part of the historic architecture of the Island and Boricua sportsmen/women.

Additionally, the video shows us: Puerto Rican pro-independence figures whose struggles against Spanish and American imperialism are not described in the slightest, the designation of Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court of the United States (something that does not mitigate the impoverishment of Puerto Ricans under the domination of that country), images of local agricultural workers of the 20th century that do not illustrate the exploitation that they suffered under American corporations and other decontextualized images of resistance. The culminating argument of the video is that “being a legend comes naturally to us”4due to the mere fact of being Puerto Rican and that there is no necessity of mounting political resistance against colonialism. A cynic would answer that the intention of local and foreign capitalists is, precisely, to convert the Puerto Rican nation into a legend of the distant past through the mass expulsion of its populace and low fertility rates that both gentrification and the impoverishment of its communities produce and without which they cannot convert the island into a touristy Disneyland.

It’s rather curious that a large part of the intellectual elite of the country has not examined the Bad Bunny phenomenon as a prime example of marketing. Said concept constitutes the practice of inserting general ideas into a product to make the consumer believe that it has more value than what it contains in reality. The systematic application of the same ideas to a series of products made by an entrepreneur or company, in turn, creates what is known as a brand. Both the practice of marketing and creating a brand are two of the most distinctive aspects of the consumer culture that corporations promote. Renaissance paintings and sculptures, for example, were commissioned directly to the artists of the age. They were not made so that the individuals from other social classes would buy them because the technology of the age did not permit its mass reproduction. According to Walter Benjamin, it was the development of technologies such as photography and cinematography during the 19th century which allowed the technical reproduction of art among the masses5 (Benjamín 2003, 40 – 41) and from that point forward, the capitalists reduced art to a consumer product that would reflect their individualist values. The rise of radio and television during the 20th century, together with the rise of digital technologies and streaming services since the 1990’s onwards, intensified that tendency.

In this context, where art is commercialized to promote the ideas of the ruling class, Bad Bunny’s success is based in his capacity to project himself as a brand; whose main ideas are individualism, profiteering, hedonism, and isolated acts of rebellion. Most of his musical repertoire, his publicity stunts (as is the cited video) and the occasional references to the Puerto Rican national reality; are the means through which those values are marketed to international consumers. His art appeals to a large quantity of employed and unemployed workers worldwide that seek a power fantasy to temporarily escape their wretched circumstances. The artist, after all was born to a working-class family and even worked as a bagger in a supermarket by 2017. But there are also many members of the wealthy classes that appreciate Martinez Ocasio’s music because it reflects the way they interact with the world. This is why he has received the patronage of Puerto Rican multimillionaire Noah Assad Byrne: who has investments in real estate, dispensaries of medical cannabis, restaurants and founded Rimas Entertainment in 2014. This Puerto Rican entertainment label specialized in Urbano music with offices in the United States, Colombia, and Venezuela has an estimated value of $1,000 million that comes out of the contracts that it maintains with figures like Corina Smith, Karol G, Arcángel, Mora, Mickey Wooz, Amennazi, Jowell & Randy, Lyanno, Marconi Impara, Subelo NEO, Urba and Rome, Bad Bunny, and many other reggaetoneros.6

Given that Martinez Ocasio operates in a corporate machine that compels him to market his music, this artist is not capable of transcending the strict individualism of his brand even when he tries to touch subjects of social criticism. For example, the song “Maldita Pobreza” (2020) narrates the frustration of a young man that is not capable of socializing due to lack of employment in spite of seven years of study; which express the tangible problems of unemployment and the subordination of the act of socializing to consumerism that are common to capitalism. But the plot is “resolved” through an individual, suicidal and futile act of blowing up the Puerto Rican Capitol on the part of the young man. In the case of “Andrea” (2022), Bad Bunny speaks about a young Puerto Rican woman that struggles to pay rent, stay in Puerto Rico and study to make her career at the same time; but the alleged resolution of the problem lies in the individualist formula of partying and sexual promiscuity. Finally, “Lo que le pasó a Hawaii” (2025) correctly expresses that Puerto Rican often see themselves in the obligation of emigrating to the United States due to the poverty that they suffer under the colonial relationship “and those who did dream of coming back”.7

The singer, however, denies worker’s capacity of resolving this systemic problem in a collective manner in this song and urges Puerto Ricans to celebrate our cultural heritage individually, something that does not threaten his own profits and those of Assad Byrne. I would even dare to say that Bad Bunny knows that his role consists in monetizing and promoting the crudest form of individualism through his music and does not care, because the lyrics of “Los Pits” (2023) stipulates in a fulminant manner that:

I could be rapping about deep stuff

But the checks arrive and I get confused8

In the end, the purpose of this essay is not to denigrate people who like Bad Bunny’s music. The fact that we are immersed in consumer culture, which is degenerate in the sense that it reflects the ideas of the ruling class and not those of the working class worldwide, does no convert us into uncultured degenerates.

It’s unfortunate, for example, that Puerto Rican intellectual Roberto Ramos Perrea insinuated that the receptivity of Martinez Ocasio’s music among Puerto Rican consumers turns us into a brutish and ignorant nation. Such an opinion appears in a pamphlet titled Sobre Bad Bunny y la monarquía de la ignorancia (2025) and I would have preferred that the author have focused more on connecting his correct observation that Bad Bunny “Is a [commercialized] product” (Ramos-Perrea, 2025, 22 – 24) with the cultural priorities of the wealthy groups. Instead of issuing empty condemnations and celebrations toward the figure of Martinez Ocasio; we have to analyze his music critically and examine the forms in which the current economic system produces it. There must be at least one question that guides this necessary exercise: Is Bad Bunny the voice of an outraged Puerto Rico or that of a minority that wants to sell us our values as if they were ours?

Cited sources:

Benjamín, Walter. (2003) La obra de arte en la época de su reproductibilidad técnica. Traducción de Andres E. Weikert. Mexico: Editorial Itaca. https://archive.org/details/benjamin-walter.-la-obra-de-arte-en-la-epoca-de-su-reproductibilidad-tecnica-ocr-2003/mode/2up?view=theater

Drowne, Kristine. (2023) “La representación de la cultura en el imaginario colectivo puertorriqueño: Cómo Bad Bunny por medio de un intro de un concierto reescribió la historia de la identidad puertorriqueña”. In 80grados+prensasinprisa. https://www.80grados.net/la-representacion-de-la-cultura-en-el-imaginario-colectivo-puertorriqueno-como-bad-bunny-por-medio-de-un-intro-de-un-concierto-reescribio-la-historia-de-la-identidad-puertorriquena/

Ramos-Perrea, Roberto. (2025) Sobre Bad Bunny y la monarquía de la ignorancia. San Juan: Instituto Alejandro Tapia y Rivera. https://issuu.com/iatr/docs/bad_bunny_rrp?fbclid=IwY2xjawHrpUJleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHea9ysE8nXssI5fT1v4EdxXO3CmGv0l_UUI1TlzLSbIe9T_eRo2wgjb9mQ_aem_BXH74uhBfMZCalqa0r-Ktg

Kind greetings, I hope you have enjoyed the article. Borikén: Cinco Siglos de Lucha is a project in development that will improve according to the demand of our readers. Please subscribe to receive more content in the near future.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. (1898) Manifesto of the Communist Party. Authorized English Translation. Edited and annotated by Frederich Engels. Second Edition. New York: National executive committee of the Socialist labor party. 40

Fragment of the lyrics of the song “¿Quién tú eres?” of the X100pre (2018) album from the singer Bad Bunny, as translated by user Taylor.

This translation, from Spanish to English, is mine.

This translation, from Spanish to English, is mine.

Benjamín, Walter. (2003) La obra de arte en la época de su reproductibilidad técnica. Traducción de Andres E. Weikert. Mexico: Editorial Itaca. https://archive.org/details/benjamin-walter.-la-obra-de-arte-en-la-epoca-de-su-reproductibilidad-tecnica-ocr-2003/mode/2up?view=theater

The information about Rimas Entertainment was taken from a newspaper article that tried to connect Bad Bunny with a Venezuelan entrepreneur to claim that the singer war financed by Venezuelan socialism. The act of offering a large quantity of data about this corporation and its founder through this propagandistic hit piece, whose claim no longer figures in the Puerto Rican government’s calculations when it comes to organizing the Residence of July 2025, demonstrate how stupid the ruling class can be. Serrano, Oscar J. (2022) “Company behind Bad Bunny grew from $2 million put up by former Venezuelan military man to $1 billion”. en Noticel. https://www.noticel.com/english/pop/tribunales/ahora/top-stories/20220801/company-behind-bad-bunny-grew-from-2-million-put-up-by-former-venezuelan-militaryman-to-1-billion/

As translated by user mimijilo from https://www.letras.com/bad-bunny/lo-que-le-paso-a-hawaii/english.html.

As translated by user Danilo from https://www.letras.com/bad-bunny/los-pits/english.html.